Mongabay.com: An Interview with Rhett Butler

By Laurel Neme, special to mongabay.com

June 16, 2010

Rhett Butler, founder of mongabay.com, spoke with Laurel Neme on her "The WildLife" radio show and podcast about what prompted him to develop his environmental website and also about some of the more interesting and bizarre stories he's pursued in Madagascar, the Amazon and around the world.

This interview was conducted in late March and originally aired May 10, 2010. The interview was transcribed by Diane Hannigan.

Rhett founded Mongabay.com in 1999 with the mission of raising interest in and appreciation of wild lands and wildlife, while examining the impact of emerging local and global trends in technology, economics, and finance on conservation and development. Mongabay.com is an independent information source, not affiliated with any other organization. Because it has much exclusive content and often is the first to report on otherwise neglected environmental stories and research, its articles are frequently used as a source by well known media outlets such as the BBC, CNN, CBS, NBC, National Geographic, the Wall Street Journal, Fortune Magazine, Business Week, Bloomberg, the Discovery Channel and more. According to Google Analytics, Mongabay.com averages over 1 million unique visitors per month. It ranks in the top 5,000 most visited sites in the U.S. and 10,000 in the world. In April 2008, Time.com selected Mongabay.com among its 15 top climate and environment web sites.

In addition to Mongabay.com, Rhett founded Tropical Conservation Science, an academic journal that aims to provide opportunities for scientists in developing countries to publish their research, and wildmadagascar.org, a site that highlights the spectacular cultural and biological richness of Madagascar. Apart from his web sites, Rhett's writing has appeared in The Washington Monthly, Yale Environment 360, BBC News, the Jakarta Post, Conservation Letters, GeoWorld, and Trends in Evolution & Ecology. In the course of his work Rhett has traveled widely in Africa, Latin America and Asia-Pacific.

An Interview with Rhett Butler

Laurel Neme: Before we talked about your travel and writing adventures, I want to start by asking what connection you and your name have to either Clark Gable, or the infamous character that he played in the classic movie Gone With the Wind.

Rhett Butler: Well, my name is Rhett Butler, which is well known because it's the main character in Gone With the Wind. But there's actually a connection between my family and the actor who played the character, Clark Gable. My grandfather actually roomed with Gable when the actor was preparing for a role as a test pilot. Gable wanted to room with a test pilot but there weren't any near the studio where the movie was being filmed. My grandfather, was the only survivor in a plane crash when he was in the Air Corps, was the closest thing the airbase had to a test pilot. He was a good person for Clark Gable to get to know to better prepare for his role. So I had that connection, plus my family name was already Butler and my parents had a sense of humor, so I was named Rhett Butler.

Laurel Neme: People won't forget it so that's great!

Rhett Butler: People tend to remember the name, so I guess it's one benefit.

Laurel Neme: I'm curious what first got you interested in the natural world.

Rhett Butler: I was fortunate to grow up with a mother who was a travel agent specializing in “exotic travel” and a father who earned an obscene number of frequent flier miles, so I had a lot of opportunity to travel. And I've always liked animals. It happened that a lot of animals were in the rainforests of the world, so I really got interested in tropical forests. As time went on, a few of the places I visited were destroyed after I visited them. That was really disheartening for me. I would think about what happened to the animals and the people who lived in those forests. So, that was really the origin for my interest in what I do now.

Laurel Neme: What place did you visit that was destroyed? How did you find out it was destroyed after you were there?

Rhett Butler: In 1990 I went to Ecuador, to the Amazon. At that time there was a lot of development going on there. I think about 8 weeks after I visited there was an article in the newspaper, The San Francisco Chronicle, about a giant oil spill that completely fouled this area I just visited. All I could do was think about all that oil coating the trees, the animals. I was only 12 at the time, but it really hit me. Then, later, in 1996, I was in Malaysia and I established contact with a researcher there. A couple months after I had gotten home, I heard from him that the whole area has just been logged for paper pulp mill. Then later it was converted to an oil palm plantation. It was one of these place I visited where I saw wild orangutans crossing through the forest, then a couple months later the forest was all gone.

Laurel Neme: In school did you study biology or wildlife?

Rhett Butler: I actually have an unusual career path. My background is not in this area. I'm more of a business, economics person, so I have a little bit different approach to looking at these issues. I've always been very recreationally interested in biology and conservation – and I'm well read in those areas – but I did not study that in school. I studied economics and math. It's quite different, but in reality, conservation is about people more than biology – interacting with people about how to practically protect these areas. Economics plays an important role in a lot of the decisions that are made that tie in with conservation. I like to conserve things for the sake of conserving them, but it's hard to make a justification without some economics or at least looking at the economics of the situation.

Laurel Neme: What gave you the idea to create this website devoted to raising awareness about wild lands and wildlife?

Rhett Butler: The origin of Mongabay was actually as a book. I was working on a book about tropical forests; it was meant for a general-interest audience, the kind of audience that reads Mongabay today. It went though several rounds of peer-reviews with an academic press, but then the press told me they weren't planning to run pictures – it was too costly. That sort of undermined the point of the book. I decided to put the book online for free on Mongabay in 1999 – ancient history in web years. That was the origin of the site and it's expanded since then.

Laurel Neme: The idea of running pictures was a deal breaker.

Rhett Butler: Yeah, I didn't set out to set up a website to attract a lot of people, I just wanted to put the information out there so it'd be freely available.

Laurel Neme: What happened? How hard was it to set up this site? How did it get to be so well known? Maybe you could give a little background about Mongabay for those unfamiliar with it. What kind of articles does it feature? Who are its readers?

Rhett Butler: Mongabay is an environmental news and conservation science website. It details what's happening in conservation, it covers a lot of journals as well as news-oriented content. Originally it was a site about rainforests, and it's expanded into other areas, but the focus is still tropical forests. It was started in 1999 and is still going strong today. It draws a little over 2 million visitors a month across all the content. It's obviously a big site. There are sections with travel photos, and a section on Madagascar, and tropical fish, but the real heart of the site is the environmental news and the tropical rainforest sections.

Laurel Neme: How did you choose the name Mongabay?

Rhett Butler: At the time I chose Mongabay because it was unique name. If you typed in "Mongabay" on the internet, there were no results back in 1999.

Laurel Neme: And now?

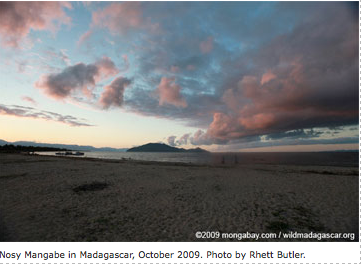

Rhett Butler: Now there are lots of results. The name is derived from an island in Madagascar. It's spelled a little differently, but it's a really interesting island. It has incredible wildlife and it's tropical with beautiful beaches. It's really a great place to visit. The island left a mark on me, so I derived the name from that island. It may not be the best name, but it's a name I chose 11 years ago and it stuck.

Laurel Neme: How does Mongabay work? Do you write everything on the site?

Rhett Butler: Until a couple years ago I wrote everything on the site. Now I have an assistant who is probably writing more than I am, at least this year. His name is Jeremy Hance. Occasionally I get contributions from other people who want to have their work published on Mongabay. But I would say around 90-95% of the content today is written by Jeremy or myself. Before 2007, almost everything was written by me. The rainforest site is based on the book that I wrote in the 90s and I've been updating since then.

Laurel Neme: How do you get your information? It often seems that you're reporting stories that are really found nowhere else, or in a very dull scientific journal and you bring them to life.

Rhett Butler: I monitor scientific journals pretty closely. I track around 50 journals a week and Jeremy Hance helps out a lot with that now. So, a lot of the content does indeed come out of journals. And there's also quite a bit of feature content that comes through my travels or personal contacts. My biggest issue now is not so much finding content, it's dealing with the content that comes in through personal contacts and things. I'm kind of barraged by potential stories coming through in e-mail. It's mostly an issue of capacity to sort through the stories and to spend the time to focus on what the readers might be interested in.

Laurel Neme: How do you choose which topics to feature?

Rhett Butler: Mongabay is, at heart, my project. It may sound a little funny, but it's topics I find interesting. Now that I've brought in Jeremy, my assistant writer, it's changed things a little bit because he can also write about things that he finds interesting. Essentially the stories are topics one of us is interested in, although sometimes there are topics that are news worthy that we don't really want to cover but feel like we should because so many people come to Mongabay now.

Laurel Neme: Like what?

Rhett Butler: Sometimes climate legislation and things like that. It's important stuff to cover, but it's really well covered elsewhere. We try to focus more on wildlife conservation, things of that nature, rather than the politics because that stuff is often covered better by other sources.

Laurel Neme: What have been some of the most interesting stories that you've pursued?

Rhett Butler: Well, recently I've done a lot of reporting on Madagascar, which is a place that is very special to me, but there's also a lot going on. Last year there was a military coup, which displaced the democratically elected president. That ushered in a period of chaos. The government structure completely fell apart. Basically, their most biologically diverse natural parks – which are rainforests in the northeastern part of the county – were ransacked by commercial loggers who were taking out high-value hardwoods. Not only were they taking out timber, but they were poaching wildlife, a commercial bush meat market developed for lemurs, which if you've ever seen a lemur it's really disheartening because they're just the sweetest creatures you can imagine. So, it's a pretty sad situation. I devoted a lot of time and effort to covering the story when very few outlets were covering it at all. I wrote dozens of articles and looked for ways to address the problem. It's still unclear to what impact it's had, but I've fed some information to activist groups and really tried to push the matter. The combined efforts of multiple groups managed to shut down the illegal rosewood trade for about three months. It was about a $500,000/day trade. It was a pretty significant achievement. Then last week, this transition authority, which is basically the coup leaders of Madagascar, announced they were going to place a two to five year moratorium on timber exports. That was a victory in this Madagascar trade issue. It's not clear whether that moratorium will be enforced, but by announcing something they're at least taking a step towards addressing the issue. That was quite hopeful.

Laurel Neme: Were there other [stories] that were particularly interesting or significant?

Rhett Butler: There was another one a couple years ago that's noteworthy. It ties in with a plan to establish a giant oil palm plantation. Oil palm is used for making palm oil. [This happened] on an island off of [Papua] New Guinea – the island was called Woodlark. What made Woodlark special was that it had a lot of endemic species and it was also mostly forested.

Laurel Neme: So, what happened?

Rhett Butler: Word leaked out that a company had bought logging rights to something like 70% of the island and they were planning on turning that all into a giant oil palm plantation without the consent of local people. Mongabay really covered that story and Jeremy Hance really led that effort. The result of a series of articles and getting those articles in front of the right people was basically, the plan [being] dissolved; it didn't go forward. Now the island is still forested. That was quite a happy moment when the news came through that the logging of Woodlark wasn't going to happen.

Laurel Neme: Wow! How do you cover a story like that? I know you travel a lot. Do you also go there, or are you on the phone all the time?

Rhett Butler: I travel a fair amount, but I can't travel enough to actually visit all these places to write these stories. Generally, I interact a lot with people on the ground. Phone calls and e-mail is the main way I cover a story. But, I do travel. I just did a month of reporting in Colombia. I actually haven't published anything on that trip yet, but I do travel to look into stories. It's on the ground reporting, but I do travel a lot to interview these people who are in these places.

Laurel Neme: Getting back to Madagascar, what first interested you in Madagascar?

Rhett Butler: What first attracted me to Madagascar was its wildlife. It just had spectacular wildlife. Lemurs, chameleons, strange creatures like tenrecs and mongooses.

Laurel Neme: What's a tenrec?

Rhett Butler: A tenrec is sort of like a little hedgehog. But they have a big variety of them. There's one that's almost like a platypus or an otter, there are some that are like moles—it's a strange family of mammals. So, that was a draw for me to Madagascar was to see these creatures. My first trip was in 1997. I had a really rough trip.

Laurel Neme: What happened?

Rhett Butler: Lots of things happened, an endless array of bad things. I got robbed on the first night of everything I owned. I was on a boat that sank. I was interrogated by police. I was attacked on the beach by a guy with a knife. It was one thing after another.

Laurel Neme: And you still wanted to go back?

Rhett Butler: That was the thing. I still had an interesting trip. I still saw a lot of wildlife and I had an unforgettable experience. A couple years later I concluded a subsequent trip couldn't be worse than that first trip, so I had to go back. My love affair with Madagascar really started with that first trip. Now I've been back several times and it's my favorite place to visit. I highly recommend everyone going there. Well, anyone who's flexible enough to deal with some unexpected difficulties at times. But, the wildlife is really great there. Once you actually interact with or see these lemurs up close, it's even more amazing that you can imagine.

Laurel Neme: What's it like? How many lemurs are there?

Rhett Butler: The number of lemurs has gone from about 50, fifteen years ago, to over 100. Basically, they're discovering there are a lot more lemurs than they originally believed. They're doing more genetic analysis and comparing lemurs that they thought were the same, but are different. There are a lot of lemurs. The amazing thing is that although Madagascar has been mostly deforested, there's still an incredible amount of biodiversity living in the little fragments of forests that remain. But what's interesting about Madagascar is that the animals are…the term is “ecologically naïve” – not necessarily afraid of humans. You can see lemurs much closer than you can see the monkeys in the Amazon. There has been less hunting. They just have a different mindset than a monkey. You can really see a lot of animals up close, which is really a special experience. It's up there with seeing big game safari in Africa.

Laurel Neme: Is there no hunting?

Rhett Butler: There's certainly hunting. I'm not exactly sure of the reason [why] they're less afraid of humans. It might have something to do with the history of predation or things of that nature. You definitely notice it's not quite the Galapagos in terms of approachability, but you can get pretty close to a lot of lemurs – close enough to see them well.

Laurel Neme: Has the movie Madagascar increased tourism to, or interest in, the country?

Rhett Butler: It's unclear. Originally that was the hope. In 2004 there were great ambitions for linking the movie to tourism in Madagascar, but I think there was a bit of disappointment in the actually number of tourists who went to Madagascar as a result of the movie. The problem is, in reality, Madagascar is at least a 20-hour flight from the United States. It's difficult to get around, most people don't speak English, it's a poor country, and it's off the coast of Africa. There are all sorts of reasons to not make it a trip you can do spur of the moment. I think that's been a big detriment. I think overall it did increase awareness of Madagascar. More people will know now that Madagascar is a real place. I think when the movie first came out people thought it was an imaginary place. I think its good to know that considering the diversity of wildlife that lives there.

Laurel Neme: What are some of the most interesting places, or stories from your travels to all these different places? I know you've also spent a lot of time in the Amazon.

Rhett Butler: The Amazon is an interesting place. There is a lot of development in parts of the Amazon, and then mass extents of the Amazon are essentially unchanged. You can fly for hours over the Amazon and see nothing but trees. But in the southern reaches, in the fringe areas, in the frontier, there is a lot of large-scale development going on. We're talking big-time development. There are industrial farmers coming down from the American heartland into the Amazon and launching farms that are ten times the size of what they had in the United States. There are giant soy farms, and the scale of them is just incredible. In my reporting of the Amazon I met a really interesting character named John Carter. He's originally a rancher from Texas. He moved to the Amazon in 1996; he moved to the real frontier and has had some pretty crazy times there. He's not at heart an environmentalist, but the destruction around him was so great he felt compelled to do something. He started up this organization that I would say is one of the most innovative of the Amazon. It probably has one of the best chances to have a large-scale impact on the future of development in the Amazon in a positive way.

Laurel Neme: What is he doing? What country is he in?

Rhett Butler: He's in Brazil. He's trying to get cattle ranchers to become part of the solution to addressing deforestation instead of just being the bad guys.

Laurel Neme: How is he doing this?

Rhett Butler: The fate of about 80% of deforested land in the Brazilian Amazon is cattle pasture. Basically, you're seeing deforestation driven by cattle ranching. The question is how to turn that around. John Carter is working on a certification system that would provide incentives for cattle ranchers to improve their environmental performance.

Laurel Neme: What do they have to do to get the certification?

Rhett Butler: They have to maintain at least 50% forest cover on their land, which is something we don't have here in the United States but in the Brazilian Amazon it's a law. So while it is a law, there is very little enforcement. In a world where there is little governance, John Carter is working on a system to ensure compliance of cattle ranchers. Beyond that, there are additional environmental guidelines that his organization is promoting.

Laurel Neme: What's his organization called?

Rhett Butler: Alianca da Terra - it means Alliance of the Earth. [It is helping to] reduce the use of fire in land clearing. Fire in the Amazon is a big deal. Most of the Amazon isn't accustomed to burning, so a small fire only a few inches high can do a lot of long-term damage to the forest. One of the issues you see in the Amazon is agricultural fires that escape into natural forest. They do significant damage and then subsequent fires can actually do a lot of damage to those trees. He's trying to reduce the use of fire as well as establish fire-fighting brigades to attack fires when they actually do break out. They're working with some of the world's leading scientists on setting up other guidelines for maintaining forest cover along waterways, and also registering ranches. If you're part of their registry, then the cattle rancher would submit to the sensing of their land. There's sort of a monitoring capacity built into the system to ensure that people are complying with the environmental standards.

Laurel Neme: Is it working?

Rhett Butler: The initiative has been in progress for six or seven years and is just now reaching the final stages. We'll have a better idea of how the system works a year or two from now. It's a little too early to say at this point. If you look at the structure of the mechanism there's good reason to think it should change things for the better because the incentives are in the right place.

Laurel Neme: Where are the cattle going? Is it for beef?

Rhett Butler: Historically in the Amazon, most cattle ranching was actually used for land speculation or just establishing claims to land. But over the last 10 years there has been a major change and more cattle is being raised in the Amazon for actual beef and leather production. It's actually become a huge industry. In the Brazilian Amazon alone there are more than 90 million head of cattle, which is almost as many cattle as in the entire United States. Brazil is now the world's largest cattle producing country and exporter by a significant amount. Most of that beef is consumed domestically, but a lot is exported and goes to Russia, China, and Europe. Not so much [of it] goes to the United States because I think we have a ban on fresh meat imports from Brazil, but some Brazilian beef ends up in processed meat products in the US.

Laurel Neme: When you've been there, have you seen a lot of wildlife like some of the elusive creatures like jaguars, or have you swum with the pink dolphins?

Rhett Butler: Yeah! I've seen jaguars and swam with pink dolphins. The Amazon is not like an African safari; it's not super easy to see animals. Animals tend to be elusive, and when they are around they tend to camouflage well. With that said, it is possible to see some animals, especially if you take the time to look for them.

Laurel Neme: Where's the best place to see wildlife in the Amazon?

Rhett Butler: The best place to see Amazon wildlife is a little bit outside the rainforest. The Pantanal, which is a giant wetland south of the Amazon – I've had great experiences seeing jaguar there. You also see other big animals like tapir and capybara, which is a giant rodent. Those are really found everywhere in the Pantanal. When you're in the Amazon itself, you're more likely to see small things like frogs, lizards, insects, and birds. But, it is easier to see larger animals outside the rainforest environment.

Laurel Neme: I was there last September and I didn't expect to see a whole lot because that's what you'd expect in a remote rainforest like that. You don't see much, but it's great.

Rhett Butler: A lot of people go in and are disappointed because their expectations are in the wrong place. You're not going to see a bunch of toucans joining you at breakfast or a jaguar taking down a tapir in front of your lodge. The wildlife tends to be cryptic and elusive. If you go in just looking for insects and trying to enjoy the overall experience, then it's probably a better approach than hoping for an African safari type trip.

Laurel Neme: You've also spent time in Africa. What have been some of your experiences? I know you've had quite a few elephant experiences.

Rhett Butler: Yeah, I've had two elephant experiences that I probably would have rather not had. One of them happened in 2007. I was in southern Kenya evaluating the area for ecotourism potential. There had been ecotourism there 20 years ago, but now a person who operates in the region is looking to reestablish low impact, community-based bird-watching tours in this interesting forest area. So we went in to walk around a bit and see what was in the forest and what the situation was like. We pretty quickly realized there were a lot of elephants in the forest, based on the amount of damage done to trees and the copious amounts of elephant dung everywhere. We went for a long hike and were returning when we got surprised by a group of elephants. [They] charged us and pursued us for quite a while. I won't get into the full details, but one of the trackers was trampled by an elephant. Luckily, [he] wasn't injured very seriously. He was pretty smart about responding and managed to get only a few puncture wounds from the tusks. He got tromped on his legs, but the soil was very soft so he wasn't crushed, it just caused some pretty significant bruising. It was quite an experience and really shows you the power of these animals.

There's also a conservation lesson in this experience. The reason there's so many elephants in these areas is that there's a lot of forest clearing right now around this area. These elephants are being displaced into smaller and smaller patches of forest. As they return to areas that were traditionally their habitat, they're encountering agriculture. Then there's a new source of conflict. An elephant will eat someone's maize or corn and then people will attack it. It's a source of conflict for these elephants. You have agitated elephants being forced into smaller and smaller areas. We walked into the middle of that situation. In any case, it was an exciting experience and we learned some lessons from it.

Laurel Neme: We heard on another episode of The Wildlife about elephant pepper being planted around crops. Elephants hate pepper and will stay out of the crops. Is anything being done in this area to deal with this elephant-farmer conflict?

Rhett Butler: I actually brought up that elephant pepper approach when I was there and they had never heard of it. They liked the idea but they didn't believe it would work. But it was something to look at! The root of this conflict is that you have people cutting down forest, which happens to be elephant habitat. You can use elephant pepper to protect against that but you still have the root problem of habitat loss. You have too many elephants with too little forest. It's a difficult situation. Maybe elephant pepper would work in some areas.

Laurel Neme: Is there tourism to try to extend the habitat?

Rhett Butler: Our tourist experience I don't think would be suitable to most tourists! They were looking at the possibility of establishing tourism there which would be another source of income for these local people – perhaps help offset the costs of having elephants around their villages. There were other activities that were being developed, like honey harvesting. Honey is a big commodity for local tribes in this area. Their method for harvesting it was not very efficient, so some outsiders have come in and introduced new ways to produce honey that will do less damage to the forest. There are also some other industries like reforestation with trees that they use for making poles that they surround their villages with. Instead of depleting the natural source of this timber, they'll grow their own. Things like that are hopeful, but in the long term tourism could help if you could really get community support and involvement in it so they could actually benefit.

Laurel Neme: Have you been gorilla tracking too?

Rhett Butler: I have gone to see the mountain gorillas in Uganda. That's an interesting model; it's a good one for conservation. The price now to see the gorilla is something like $500 a day for a permit, which is obviously a lot of money. It's a problem in that it's not very democratic and open to everyone, but it generates a lot of money for gorilla conservation. Some of that money goes back to the local communities through direct payments, but also by hiring local people as anti-poaching patrollers, porters, park rangers, and things of that nature. The benefit is you have money coming in for low impact tourism. So, you get a lot of bang for a relatively small amount of visitors.

I've also seen gorillas in a less structured environment in West/Central Africa. Those are the lowland gorillas, which are far more abundant, but are facing a different sort of population trend. They're unlike the mountain gorillas, which are increasing in population. The lowland gorillas are being hit by the bush meat trade, Ebola outbreaks, and habitat loss. While there are a lot more of them, they are decreasing in number. My experience with the lowland gorillas was a bit wilder. I was charged by a silverback, which was quite a hair-raising experience. Having a 500-lb animal charge by you several times beating its chest is enough to get your heart racing.

Laurel Neme: What country was it that you were in?

Rhett Butler: It was in Gabon. I was with some local rangers and unfortunately for me I happened to be the tallest person so I stood out as the dominant male of the group, even though that wasn't necessarily the case. That's how the gorilla saw me. He picked me out as the male he needed to show his dominance over. It was quite a humbling experience.

Laurel Neme: What did you do as you were being charged by this silverback? Did you hold your ground? Did you beat your chest too? (laugh)

Rhett Butler: No, I think that would have been a bad idea. (laugh) I was down on the ground. I got down on my knees and put my head down to be submissive. That solved the problem. I wasn't injured in any way. He ran by me beating his chest probably eight or nine times. He let down his guard and we all quickly exited. We were just hiking; we weren't necessarily seeking out the gorillas. We just came upon this group somewhat unexpectedly. It wasn't an arranged experience; it was very raw.

Laurel Neme: What were you doing in Gabon? You've had a lot of wildlife encounters [there], is that right?

Rhett Butler: Yeah, that was my first trip to the Congo Basin. I went to a national park on the coast that's fairly well managed and pretty well known. It's called Loango. They actually did a Survivor [TV show] there a couple years ago after I went. It was my first time to the Congo rainforest; it was definitely an interesting experience. You're a lot more cautious when you walk around that forest than in South America or Asia. There's a lot more animals that can get you there.

Laurel Neme: Are there a lot of elephants there too? I've heard of a lot of studies done there regarding poaching.

Rhett Butler: [That very park] is a major research center for the Congo Basin. They have forest elephants there and I also had an experience with forest elephants on that same trip where we were charged, but it was nothing as dramatic as the time in Kenya. After that I actually went through the process of learning what to do when charged by elephants. Of course in Kenya I promptly forgot all of that.

Laurel Neme: What are you supposed to do when you are charged by elephants?

Rhett Butler: There are different approaches. The easiest thing is to probably get behind a very large tree. That's what I tried to do in Kenya but unfortunately none of the trees were large enough. A small tree an elephant will run right through, so it's not going to help you much. The other things I was told is you can stand very still, which, when an elephant is charging you, may be a little bit challenging to do. You can also throw something for the elephant to go after, like a sweater or jacket, and wait for it [to attack that object] while standing still. I don't if I'd subscribe to any of those approaches in reality just because when you have a several ton elephant running towards you it's going to be tough to stand your ground or have the presence or mind to distract the elephant by throwing a jacket or something. I would almost always go for the tree option if possible. In Gabon you can also hide in the roots of a stilt palm tree. Some people refer to them as an “elephant protection tree” because you can get inside and the elephant can't do much damage to you.

Laurel Neme: Are there snakes and other things that hide in the stilt palm trees? As you're getting safety from the elephant…

Rhett Butler: That probably wouldn't occur to you when you're running from an elephant. Unfortunately, the option that works in some cases is just to outrun everyone around you. It doesn't work with elephants because I believe they run faster than people.

Laurel Neme: Has is ever occurred to you that elephants just don't like you? (laugh)

Rhett Butler: (laugh) Well, I've only had those two experiences. In neither case were we approaching the elephants and doing something we weren't supposed to be doing. The second time we were completely ambushed and surprised by the elephants and the first time there was a calf around; I'm not sure what happened. In neither case were we trying to find elephants. They found us.

Laurel Neme: (chuckle) So you don't take it personally?

Rhett Butler: (laugh) No.

Laurel Neme: You've done, in my mind, some extremely interesting interviews. It's really amazing to have all that. I'm wondering if any of those interviews in particular stood out?

Rhett Butler: I've done several interviews with Dan Nepstad who works with the Woods Hole Research Institute. He's an expert on the Amazon. What's interesting about Dan is he does both macro and micro stuff. He's looking at the entire ecosystem and then he's also looking at very small elements of the ecosystem. He's done such a broad and diverse array of research that really ties in with big picture issues of the Amazon. He's one who is working with John Carter, the cattle rancher from Texas, who's now developing a certification scheme to improve the environmental performance of cattle ranching. That effort was a collaborative one between the two of them. But Dan is also looking at the long-term impacts of climate change, specifically drought in the Amazon. What he's finding is somewhat terrifying: just a few years of drought can leave the forest susceptible to forest fire and die off from stress. It raises a lot of concerns. But Dan is also hopeful of the potential of reducing the impact of certain types of activities in the Amazon, like the certification system. He's also looked at payments for ecosystem services. [He is] looking at the value of carbon and also water in the Amazon with the hope of providing incentives to landowners to not cut down forests. My interviews with him have really stood out. I've also had some interesting interviews with Andrew Mitchell of the Global Canopy Programme. He's a scientist, but he's gotten increasingly interested in the payment for ecosystem services concept. Again, it aims to unlock the value of ecosystems, but specifically forests in this case, as living, healthy entities. For example, capturing the value of the water they provide, erosion control, the carbon they store, all these things we generally take for granted from the ecosystems around us but actually have a tangible value.

Laurel Neme: In terms of Mongabay and the reporting of these types of activities, because they aren't really well known or well reported elsewhere, I'm wondering about the general impacts or advantages of being an online news source.

Rhett Butler: A big focus of Mongabay is education and outreach. I have a site for children that has been up for six or seven years that reaches a lot of kids every month. I've made a big effort to have that site put in multiple languages. It's now in 33 languages. The idea is to make this information freely available to as many people as possible. I have PDFs [of web pages] so it's easy to print out a copy and hand it out at schools. I've actually encountered people out in the field who have Mongabay materials printed out for kids in a remote village.

Laurel Neme: That must be heartening!

Rhett Butler: Yeah, it's happened in Madagascar and Thailand. It's very much a surprise when I see it. It's the whole point of what I'm doing; that's the education component of Mongabay. I'm planning this summer to do a lot more work in that area and bring in some teachers to help with the effort. That's one of the many projects that aren't necessarily apparent on the website. But, in terms of the advantages of being online, production costs are a lot lower. It's fairly easy to disseminate information and update it. I can go back and improve the children's site as more research becomes available or I get feedback from teachers. As I travel around, I see that the internet is definitely expanding throughout the world. There is better access in places that were once very remote. Someone will have a cell phone where they can access the internet. So, this site is a very basic site. There is no Flash, just very simple HTML code, especially the children's site. It tends to load very quickly in bandwidth-constrained environments. That's one of the goals of the site is to make it as accessible to as many people as possible, especially the children's sections.

Laurel Neme: Have you seen a lot more competition for this kind of site? Over the years, especially recently, you've seen a lot of environmental reporters losing their jobs and established news organizations switching to online-only editions or folding entirely. How has the recession affected the site?

Rhett Butler: There are two issues there. In terms of competition, I don't spend a lot of time looking at websites. I'm too busy; I don't know the competitive landscape for Mongabay that well. I do notice a lot more green-oriented sites out there. They seem to be disappearing now given the recession, but I'm not too worried about competition. The goal of Mongabay is to reach out and spread awareness. If there are more sites spreading awareness about environmental issues – and doing it accurately, if they're not doing it accurately then that becomes problematic – then, they're just out there spreading the word, and that's great. That's the mission of Mongabay – to do outreach.

In terms of the recession, it's had a major impact on Mongabay. It seems like a lot of green advertising networks and also green-oriented websites are shutting down or scaling back because, from my standpoint, I've seen a huge decline in advertising. I think there's been a general pull back in ad spending in the green sector especially. As the economy soured, people are going to be spending less money on more-expensive green products. I saw a huge drop off in advertising in late 2008. I live very modestly and my expenses are low, so it's not hard for me to not draw a salary for a few months. It's not hard for me to save money and spend it wisely. But if I were a large corporation with a large payroll, it would certainly be a difficult time. As a small operation I can not draw a salary for six months and get by, but if you had 10 or 20 employees it'd be much more challenging I think.

Laurel Neme: What had your experience with Mongabay taught you, or what can it teach others in the environmental news business? It has huge exposure. It seems like a lot of environmental journalists are struggling with exposure and making it a viable economic enterprise, as well as getting the information out there and getting it right. It seems like a lot of information content has exploded, [like with blogs], but information accuracy hasn't necessarily followed suit.

Rhett Butler: There's a lot of rewriting of content. When people rewrite it, they sometimes get it wrong. I get frustrated when I see Mongabay content get misrepresented. Details get left out which then makes the content inaccurate. There's a lot of misinformation out there. I'm amazed by newspaper columnists that can write things that are completely inaccurate and there's no repercussion. They have an established column and they can basically make up what they want from a scientific perspective and pass it off as legitimate content. It blows my mind that there's no check system, or any way of policing that, or repercussions for these columnists. You can see it a lot with climate change writing. In the Amazon there was the “Amazon-gate” scandal, which, from all I can see, there was no scandal. The IPCC cited a report by WWF, which they shouldn't have done, they should be citing the scientific research because there's nothing wrong with the underlying scientific research, but now it's being passed off as some big scandal. The columnists writing about this issue have been getting the facts quite wrong. They're obviously not even looking at the original research, they're just spinning it. It's mind-boggling. There's no downside for them. They are still writing these columns. There's no reason for them to stop if they're not going to be called out on it. I mean, they're called out on it on blogs, but their audience is a lot bigger than the people that read those blogs.

Laurel Neme: If someone wants to get into the job of writing about wildlife, what advice would you have for them?

Rhett Butler: From a financial standpoint, starting a new blog is a challenging endeavor. The economics aren't very good right now. I'll be honest; it's a tough environment. I definitely wouldn't get into it for the money.

Laurel Neme: Good advice right there!

Rhett Butler: If you're really passionate about the issues, and are happy to pursue it because you're passionate, then that's great. If you're a good writer and can tell good stories, then starting a blog might be a good way to land an actual paying job somewhere else. If you build a following, you may be able to land freelance work, write a book, latch on with a news organization, or even join a conservation group that's looking to tell their story better. I would certainly encourage people to develop their writing and look for stories. Start up websites or blogs, but just be aware that it may not necessarily be a very profitable endeavor. You should look for the other potential benefits rather than making a lot of money from running a website. From experience, it's not a super profitable endeavor. I still haven't made as much money on an annual basis from running Mongabay as I did when I first left school to join a consultancy when I was twenty years old. I'm certainly not in it for the money.