National Geographic: Did Polar Bears Really Lose at CITES?

Delegates at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) 16th Conference of Parties held in Bangkok in March rejected a proposal to ban international trade in polar bears and their parts. The decision caused a stir because polar bears face a precarious future.

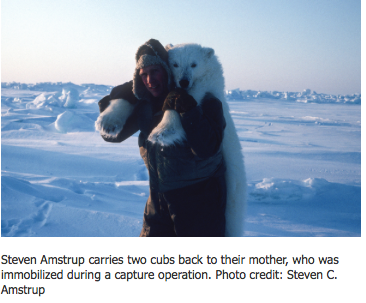

While some non-governmental organizations, such as the Humane Society International and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, were deeply disappointed by the failure to uplist polar bears from Appendix II to Appendix I, which would have banned all international trade in the species and their parts, Steven Amstrup—a renowned polar bear scientist—believes that limitations on trade don’t address the real challenge facing the iconic animals.

He argues, as does the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group, that international trade restrictions would have little conservation benefit because the primary threat to polar bears, by far, is rising temperatures and the subsequent loss of sea ice. (See “On Thin Ice,” by Susan McGrath, National Geographic, July 2011)

Amstrup has been studying polar bears and their habitat since 1980. Much of what we know about them, and even how scientists study them, comes from his work. He joined Polar Bears International as a senior scientist in 2010. Before that he was Polar Bear Project Leader with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) at the Alaska Science Center. In 2012 his lifetime contributions were recognized when he was awarded the Indianapolis Prize, a “Nobel Prize” for animal conservation.

I talked to Steven Amstrup about the CITES decision and the fate of polar bears. The conversation was transcribed by Dustin Circe. You can listen to it in full at www.laurelneme.com/wildliferadio.

Laurel Neme: Were you involved in the proposal at the CITES convention put forth by the United States to uplist polar bears from Appendix II to Appendix I that would basically have banned all international trade in polar bears and their parts? What did you think of it?

Steven Amstrup: I was not involved in drafting the proposal at all. I no longer work for the U.S. federal government, and these kinds of proposals are typically put forward by agencies, or agencies collaborating with other organizations.

The proposal was put forward based on the threats to polar bears. However, the further limitations on trade have nothing to do with the global warming and the disappearance of polar bears’ habitat. In fact, I sometimes wonder if these proposals couldn’t actually become a distraction from the main thing we need to focus on, which is reducing our emissions of greenhouse gases.

Laurel Neme: Did you expect it to pass? Would it have helped elevate the issue, even though it wasn’t the trade that was hurting the polar bears but that trade was yet one more thing hurting them?

Steven Amstrup: Actually, I didn’t know how it was going to go. The CITES conventions are often as much politics as they are science. The science is very clear, that all polar bears ultimately are threatened with extinction. Unless we come to grips with emissions, and reduce them, we are going to lose all polar bears. I think all the scientists in the world who are most familiar with the knowledge that we currently have about polar bears believe that that’s the case. Will there be some polar bears that may survive in some small pockets for some small time? Maybe, but it’ll be nothing like the extent and numbers of polar bears that we have now.

So the people who put forward this proposal are thinking about the future of polar bears. But restricting legal trade across international borders has no guarantee of affecting harvest, and affecting harvest is not really the problem. In 2010, I wrote a paper that ended up being published in Nature, and my colleagues and I showed pretty clearly that saving polar bears is all about stopping temperature rise. Only if we get our act together and do that will these on-the-ground measures, like restricting hunting, restricting human access to certain areas in the Arctic, be effective if we also are lowering our emissions.

Further, with regard to CITES, the limits on international trade are not necessarily or obviously linked to reductions in harvest. I think there’s an assumption that if the people who harvest polar bears have fewer avenues for trading their skins and other parts, maybe fewer of them will be harvested. But trade within countries—and the main country that harvests polar bears is Canada—is likely to continue. In Canada polar bear hunting is a very important part of aboriginal culture. It’s not clear that restricting trade would confer a conservation benefit. And it is clear that it would likely alienate many of the people we would like to have as allies in the fight against global warming. These are the people who live in the Arctic and who, like polar bears, are the main victims of global warming that’s caused by you and me living in lower latitudes. So I think the main emphasis in trying to uplist polar bears from Appendix II to Appendix I is a little bit displaced.

That isn’t to say that the people who proposed it aren’t genuinely concerned about the future of polar bears. I think they are. But I know that I would like to see the kind of energy that was going forward by various governments to uplist polar bears in CITES, I’d like to see that same amount of energy at the government level to address greenhouse gas emissions. That’s what we really need to do to save polar bears.

MISPLACED PUBLICITY?

Laurel Neme: Do you think having this proposal, and having some press on it, has raised the awareness of people about global warming, even though it wasn’t adopted? Or was it misplaced publicity?

Steven Amstrup: I have mixed feelings about that. The logic that I just used is, if we restrict trade, is that likely to reduce harvest and is that likely to result in some prolonging of the ability of polar bears to live in certain areas? My conclusion is that it probably isn’t. But like all models, that could be incorrect. Unfortunately, I don’t see much in the general media about what assumptions are going into the various negotiations. And what I really see is a lot of emotion about, “Well how could you possibly go out and shoot these beautiful animals that are threatened with extinction?” And that’s the wrong level of what we need to be talking about. We need to be talking about the real root cause of the threat.

Polar bears, like other wildlife, are renewable resources if they have stable habitat and are managed in a sustainable way. I think we can’t lose sight of that, and we can’t lose sight of the fact that many cultures have a history going back thousands of years of hunting these animals. So we need to tread very carefully if we’re going to adopt a large umbrella piece of legislation like CITES uplisting that can affect the lives of lots of people.

Unfortunately, the media attention I’ve seen on this has been largely, “Oh well, how could they not be uplisted because they’re a threatened species or they’re an endangered species?”—and there has been very little in the way of discussion about what that really means or why polar bears are endangered and what we really need to do to save them.

Now, I’m not going to say that at some point in the future we won’t want to just pull out all the stops we can: banning international trade, closing off hunting seasons. All of those things may eventually be on the table. But for the foreseeable future there are a number of populations that we can probably harvest safely (I don’t want to say sustainably because that suggests perpetual balance between harvest and stable populations). But they can be harvested for a number of years before global warming begins to negatively affect their habitat, like it is the habitat in Alaska or Hudson Bay now. So there are places where bears can safely be hunted for some time to come, in a transient sense. And to stop that hunting globally [and ban international trade] because we want to address a belief that somehow [it] will allow us to get to the root answer of reducing greenhouse gases, I’m not sure there’s much logic there.

Laurel Neme: The IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group disagreed with the U.S. proposal to uplist polar bears for the same reasons you mentioned. You are a member of that group, correct?

Steven Amstrup: Yes, and I was on the drafting committee of that position statement.

WALK SOFTLY TO SAVE BEARS

Laurel Neme: What’s next to protect polar bears? What can people do to help? You’ve been quoted as saying “polar bear conservation can’t occur in the Arctic.”

Steven Amstrup: That really is the crux of it. The traditional model of conservation has been that we can build a fence around an area, we can keep people out, we can control hunting, and then we can go home at night and sleep well, thinking that we have saved this species or habitat.

But you can’t build a fence to protect polar bear habitat from rising temperatures. And that’s what we’re faced with. The only way to save polar bears is for you and me and everybody else we know to walk more softly on the Earth, to recognize that we have to use less carbon-based energy.

The situation with global warming is relatively straightforward. You hear a lot in the news about the uncertainties—how soon it’s going to be a certain temperature in a certain locale, or when is the first summer that the sea ice is going to disappear entirely in the Arctic. These are questions that scientists can’t predict very well because of the tremendous amount of chaos in the climate system.

That chaos is going to continue, and it’s going to prevent very precise kinds of predictions like that. That chaos is going to be occurring over a higher and rising [temperature] baseline. And so the only reason that the uncertainty created by the natural variation, or chaos, in the system is important is if we don’t care about the future that we’re leaving for our children and grandchildren. Because it will get warmer.

You can think of this as a threshold exceedance issue. We may not be able to say the first year the sea ice is going to disappear entirely in the Arctic, but we know with absolute certainty that it will if we stay on our present greenhouse gas emissions path. And so, to me, a lot of that uncertainty, or all of that uncertainty, is largely irrelevant because we know we’re on a bad path. We’re on a very bad path. We’re on a path that very soon will take us far off course of a climate to which humans have become accustomed and in which they thrive. And yet we’re just proceeding along and not doing anything about it.

A VERY BAD PATH, BUT IT’S NOT TOO LATE

Laurel Neme: Is it too late to save the polar bears? Are we on that path? Can we change that?

Steven Amstrup: We are on the path that will result in polar bears being eliminated. But my work and the work of many others has shown that there is still time to save them.

We have to acknowledge that we’ve already probably put enough carbon into the atmosphere that some polar bear populations, at the southern extent of their range or in areas where warm currents affect the sea ice, those may disappear because of emissions we already have released. But we still have time to save many of them. That was one of the outcomes from my paper in Nature.

We still have time. However, every year we delay puts us farther down that path, and at some point, it’s going to be too late to act. Because the warming that we’re putting into the atmosphere now is not felt immediately, there’s a latent effect. The ocean absorbs a lot of the heat. Ultimately, the temperature that the Earth will achieve based on a certain amount of carbon being released this year won’t be felt for 20, 30, 40 years. So we need to recognize that the farther into the future we go, the closer we get to crossing some of those thresholds that we aren’t going to like very well.

Laurel Neme: If people ask their congresspersons for a less carbon-based energy policy, or to fund research and development, as well as taking their own actions to take more public transportation, that all would be helpful. Correct?

Steven Amstrup: Absolutely. The bottom line is that we really need to pay the hidden costs of relying on carbon. We have basically grown our society, grown our culture, by subsidizing it with the primary productivity of the past. That is, the oil and gas and coal that’s been in the Earth for millennia. We’re bringing it out and putting it back into the carbon cycle.

What we need to do is say, okay, to the extent that we’re going to continue to use carbon-based energy, we need to pay the full costs. And the full costs are the things that we will be imposing on the people in the next generation—and the polar bears.

I think the real lesson is that we can coexist with these creatures. We have the ability to change our ways so that we can continue to have polar bears.

When you’re flying over the sea ice in a helicopter, and you look down, and it’s all this rubble—from a high altitude it looks almost like the surface of a cracked eggshell—and you look at that and think how could there be any life down there? Then you get down there, and you realize that these giant white bears have figured out a way to not only survive out there but to thrive and to become the biggest of the non-aquatic carnivores. To me, that’s just so impressive.

I have to think that we, as humans, who are in total control of whether or not those giant creatures continue to exist, will take the action necessary.