National Geographic: Elephant Foster Mom: A Conversation with Daphne Sheldrick

Orphaned elephants “can be fine one day and dead the next,” says Daphne Sheldrick, a Kenyan conservationist and expert in animal husbandry.

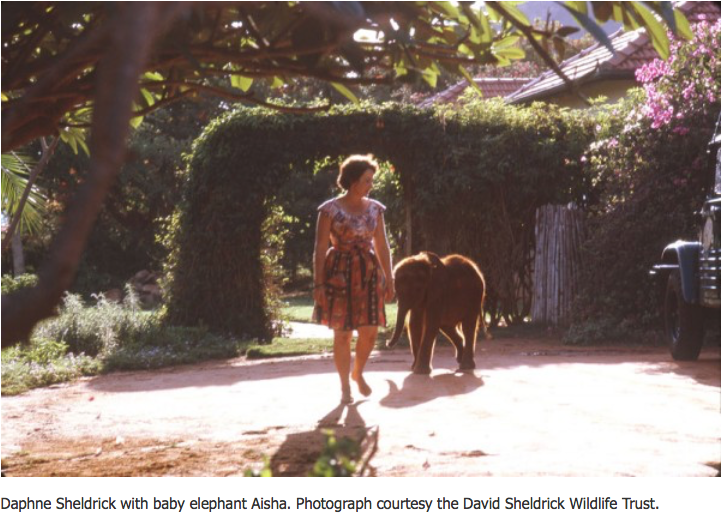

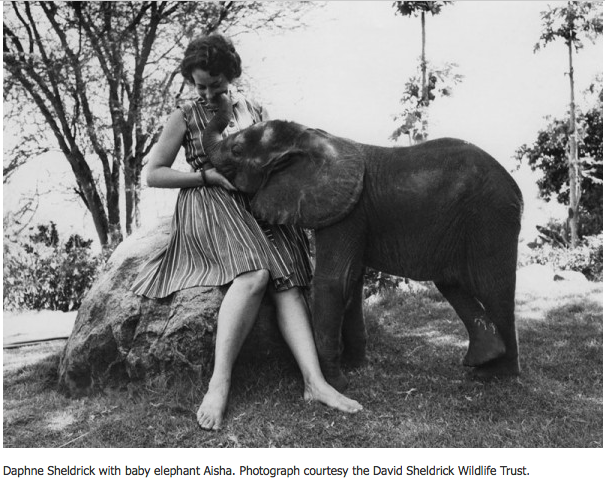

She knows. To date, she has fostered over 250 calves, first in partnership with her husband, David Sheldrick, founding warden of Kenya’s Tsavo East National Park and a legendary naturalist, and later (following his death in 1977) as part of the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (DSWT), which she founded in his memory.

Many are victims of poaching, like one-year-old Lima Lima, who was found weak and dehydrated. When she arrived at DSWT in February, Lima Lima was very thin and sickened from browsing on the invasive prickly pear plant (which can be poisonous) during her abandonment.

Lima Lima took milk from a hand-held bottle and was warmly greeted by the other elephants at the nursery, but she mourned for her lost family and often secluded herself, which is natural behavior for an older orphan who has gone through such trauma.

This year Kenya has lost some 250 elephants, with many infants and young left behind. Just in 2013, DSWT has taken in at least six calves orphaned by poachers, and another half dozen for reasons unknown (but likely poaching victims too).

Raising rescued elephant calves is challenging, and mortality rates are high. Part of the difficulty is that infants are fully dependent on their mother’s milk until they’re two years old and are not fully weaned until around four or five.

Baby elephants can’t tolerate the fat in cow’s milk. Finding a suitable substitute for elephant milk took Sheldrick 28 years of trial and error before she hit on a formula that contained coconut oil—likely the nearest replacement for the fat in elephant milk.

But as Sheldrick has seen time after time, raising an orphaned elephant requires not only meeting its physical needs but also its social and emotional ones.

Many are severely traumatized by what happened to their elephant family and “just want to die,” Sheldrick says. That’s why each new rescued elephant becomes part of a new “family” of keepers and other elephant orphans at DSWT.

Sheldrick talked to me about her experiences raising orphaned elephants and returning them to the wild. While best known for this work, she and DSWT do much more, including raising the orphans of other species, such as rhinos, helping with anti-poaching efforts, advocating against the ivory trade, and providing medical care to injured animals in the wild.

Sheldrick’s memoir, Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story, tells more stories about her life and the orphans. The DWST website provides current details and videos about the organization’s work with the orphans. You can also read National Geographic’s recent article about Orphan Elephants.

Daily Routines

What is your typical day?

My day begins at 5 a.m., when I get up to do my own housework, and when it is quiet and peaceful. The orphans leave their night stockades at 6 a.m., after their first milk feed of the day, and head out into the forest behind my house, which is within Nairobi National Park.

Each orphan has a book where all the feeds are recorded, as well as consistency and frequency of stools, plus any other information relevant to the health of the individual. I study each book first thing in the morning to see if anything unusual is recorded, such as loss of appetite, not sleeping well, nightmares, etc. That might be an indicator of things going wrong.

Baby elephants are extremely fragile. They can be fine one day and dead the next. That is where experience comes in—just being able to detect any such signs early enough to do something about it.

I then put food out for the birds and squirrels before bathing and getting dressed.

By 8 a.m. I am ready for work, like everyone else. I liaise with Angela [Sheldrick’s daughter and the director of DSWT] to catch up on events, before starting work in my office dealing with the e-mails that have been passed over to me to answer. (All e-mails go to Angela first, who then delegates.)

At 11 a.m. the public visiting hour begins. Items for sale in aid of the orphans are displayed on a table, and the public begins filing in, each paying KSh 500 [about US$5.75]. The fee supports the orphans and [finances] the conservation fee that the Trust is obligated to pay the Kenya Wildlife Service monthly. Local schoolchildren, who come in free of charge (in their hundreds), access the orphans through another pathway at the other side of my home.

The orphans are brought into the compound in front of my house for their noon milk feed and, weather permitting, a mud bath. During that time the public stands behind a cordon in order not to crowd the elephants.

The elephants come in two sittings, the smaller orphans first, followed by the older ones. Each lot spends half an hour at the site so that the visitors can enjoy their antics, which include playing and rolling in the mud, some enjoying a game of football with the keepers, others taking a dust bath, etc.

At noon the elephants leave the compound with their keepers. They are out in the park until 5 p.m., when they return to their night stockades. [At that time] people who have supported the project by fostering one of the orphans are allowed to visit them and watch them being put to bed for the night.

Hanging outside each stockade or stable is a bucket, where the three hourly milk feeds are put throughout the night, [with] one of the keepers assigned to night milk-mixing duty.

What is a typical day for an orphaned elephant infant?

A typical day for the infant elephants revolves around their three hourly milk feeds and keeping them as happy as possible.

Keepers are with them 24 hours a day. A different keeper sleeps with a different elephant each night to ensure that no unhealthy, very strong bonds are forged. That could impact negatively on the baby elephant when a keeper takes time off, as he has obviously to do.

During the nursery stage, the baby elephants follow their human family, respond to tone of voice, etc. The keepers treat them only with tender loving care, as would their elephant family, because with elephants one reaps what one sows, and since they have very long memories, they must never be ill-treated in any way. Our keepers never carry even a twig.

Because the elephants love their keepers, they want to please them and act accordingly. They are incredibly smart, much more so than a human child of the same age, bearing in mind that at any age an elephant duplicates its human counterpart in terms of age progression.

Transitioning to the Wild

When is an elephant ready to move to the next level?

As to how we decide when to move an orphan from the nursery, that depends upon the individual. It is moved when it has healed completely and is over any post-traumatic stress. We never know how many elephants we will have at any one time. With the poaching as it is, they are coming in thick and fast.

What happens when an orphan transitions to the next level?

The orphans are ready for the transition to Tsavo when they have healed psychologically and physically, usually around about the age of two years. However, elephants are totally milk dependent if orphaned under the age of three, and they need some nutritional help up until the age of five.

We now have a specially designed truck to move the elephants from the nursery to the rehabilitation centers run by the Trust in Tsavo. It has a large side panel that folds down against the loading bays, with three spacious compartments inside, so we can move three elephants at a time. It is air-conditioned, has special suspension, and space around the compartments for the keepers to move during the journey, as well as space for all the paraphernalia that must go too—milk, bottles, fodder for the journey, and so on.

What happens when orphans arrive at the rehabilitation center?

Somehow, at the other end, the ex-orphans, who are now living free as perfectly wild normal elephants again, know when others are on their way. They return to the compound to greet newcomers.

Every time nursery elephants are being moved from Nairobi, the ex-orphans mysteriously somehow know, and return to the stockade compound awaiting their arrival.

How they know this is one of those mysterious elephant mysteries that will never be fathomed by us humans. But it happens every time, even if the newcomers have never met any of the ex-orphans before, and even when the date of the move happens to change, and we have been unable to inform the keepers at the other end. Somehow, the ex-orphans always know.

I am convinced that elephants also have telepathic abilities and can read the hearts and minds of those they love, and that includes their keepers!

How amazing that the wild ex-orphans welcome new orphans! What happens with the older orphans already at the rehabilitation center?

There to greet newcomers are also all the keeper-dependent older orphans who have already been upgraded from the nursery. The newcomers are always lovingly embraced by the others, who gather around them to comfort and reassure. They surround them as they are taken out into the bush to browse for the rest of the afternoon after arrival, are with them when they go into their communal night stockades as a group and are fed their night milk feeds.

Gradually a change takes place. Rather than following their keepers, at the rehabilitation centers, the elephants begin to make their own decisions about where they want to browse, and the keepers merely follow the elephants.

When does an orphan fully transition to the wild?

Each elephant decides when it is sufficiently confident to make the transition to a wild life, encouraged by the ex-orphans, some of whom will turn up in a splinter group to escort a newcomer off for a “night out.” If during the course of the night, the newcomer decides he or she wants to return to the custody of the human family, one or two of the ex-orphans will escort the youngster back to the stockades and hand him or her over to the keepers again.

By the Numbers

How many elephants does DSWT have at each stage now?

Currently in the nursery we have 25 infants at the Northern Rehabilitation Center in Tsavo East, another 25 still keeper dependent, and at the Southern Rehabilitation Center in southern Tsavo East, another 17 still keeper dependent. Living wild are now over 70 ex-orphans, who, between them all, have about 12 wild-born babies.

How many orphaned calves has DSWT raised over the years? How many have survived? How many are now living in the wild?

We have successfully hand-reared over 150 orphaned elephant calves to date who have survived, and have lost about another 100 who came in too far gone for us to retrieve. Our three Mobile Veterinary Units have been able to save another 800 elephants, none of whom would otherwise have survived without our help. So we can proudly say that, with the help of caring public supporters from all over the world, DSWT has been able to save almost 1,000 elephants, which would certainly have otherwise added to the country’s death toll.

Quality Keepers

How many keepers does DSWT have?

We have about 58 trained elephant keepers.

Keepers do far more than tend to the elephants; they serve as ambassadors and share stories too. How do they share information?

The keepers write the Keeper’s Diary, which records everything interesting that happens on a daily basis. That way they learn about elephants and disseminate that information to their friends and family. The public viewing at the nursery is another way of passing on information, but the monthly Keeper’s Diaries inform the global public, because they are posted on our website monthly.

What is the training for a keeper?

The training is simply being taught how to handle the calves, how to mix the milk, how to recognize anything unusual in the stools, or the appetite, and simply common sense and powers of observation, at which some are better than others, and some more caring than others.

Those more caring are most loved by the elephants. One can tell who is a good keeper simply by observing how the orphans respond to them.

While each keeper is special, who have been some of the most gifted? For instance, tell me about Mischak Nzimbi? What are their stories? What are the special talents and qualities of a keeper?

Elephants can read one’s heart. Those keepers who genuinely love their charges are special, such as Head Keepers Edwin Lusichi at the Nursery, Joseph Sauni down at the Voi Rehab Station, and especially Banjamin up at the Ithumba Rehab Centre. Mishak also has a special empathy, which is recognized by the elephants he handles. Some keepers regard their work with the elephants just as a job and a way of earning money; others genuinely care for and love the elephants. As I said before, with elephants one reaps what one sows.

Emotional Connection

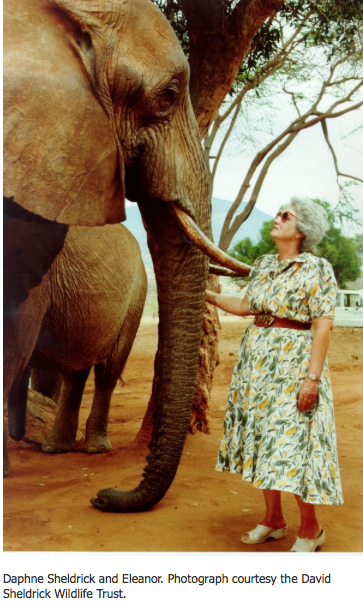

What have been the most powerful examples of memory in elephants that you’ve seen? In your book you talked about Eleanor greeting her ex-keeper, despite not having seen him for 37 years.

Eleanor greeting her keeper after such a long period of time was a powerful example of elephant memory. The orphans will even recognize people they have known fleetingly in the nursery, selecting those who have cared most for them, and paid them the most attention. The orphans also recognize one another after separation when some are upgraded, and others left behind in the nursery.

I understand that elephants who are raised in the nursery and now live in the wild will bring back their own calves to “meet” their human family. Does this always happen?

Certainly all the nursery-reared orphans, who understand the origin of the calves that are relocated to the rehabilitation centers, have brought their wild-born babies to share with the keepers, who remain based at the rehabilitation centers.

Those who have been reared at the rehabilitation centers, and who never experienced the nursery, do not, because they suspect that we might have “snatched” the calves from the rightful mothers, as elephants from disrupted populations are prone to doing.

You’ve said, “When you raise an animal, you learn the inside story of that animal.” Who are some of the animals that have touched you the most? Who did you most connect with on a spiritual level?

When one has a human child, whom you see every day and raise from the moment it is born, one knows the “inside story,” that is, the mind of that child. It is the same with orphaned animals. Rearing the orphans one learns far more about them than any casual observer will ever know, because one learns how they feel and how they think.

The stories of some of the orphans who have touched my heart are recorded in my books. I love all the orphans, but the antelope orphans are some of the very special ones that I have been privileged to know intimately and have found fascinating and wonderful.

All animals are that, but the elephants are the most human emotionally. They are just like us but better than us.

Elephant calves are very fragile in early infancy and “can be fine one day and dead the next.” How do you handle loving and caring for an infant and watching it fade? Does it ever get easier? You’ve said, “Elephants have the courage to turn the page and focus on the living.” What have you learned from that?

We draw our emotional stamina from the elephants themselves, who suffer tragedy and heartbreak on an almost daily basis, but who find the courage to turn the page, and focus on the living after grieving just as acutely as us humans, and perhaps even more so.

Whenever we are faced with tragedy and death, after copious tears, one simply has to take one’s cue from the elephants, and we do. There will be others that need your help. It would be very selfish to simply turn them away because one finds it too painful to try to help them. So one has to simply focus on the living, rather than the dead, knowing that the dead are beyond any more suffering and pain, and that one has, at least, afforded them a comfortable end surrounded by compassion and love.

You’ve said, elephants “are just like us but better than us.” How? If we could have three “elephant” qualities, what would they be? For instance, what can elephants teach us (humans) about family, nurturing, and care?

Elephants are much more caring than us humans, even in infancy. All comfort and care for those younger. They have better powers of forgiveness than us humans, despite “never forgetting,” which in elephants happens to be true. They are much more welcoming of strangers. All the orphans instantly embrace and love any newcomer, showing caring and compassion by gently touching them with their trunks, etc.

Tea Time

You describe in your book, Love, Life, and Elephants, how teatime was a special ritual:

Teatime was a fixed routine in our home, much loved by all the orphans because not only did the rattle of teacups indicate that the afternoon walk was imminent but it also meant the appearance of the teatime biscuits I baked, made from a recipe handed down from generation to generation in my family. Most of the orphans viewed these as a treat, particularly Jimmy [a kudu] and [his best friend] Baby [a feisty eland]. Gazing over the verandah ledge with drooling mouths and looks of such longing in their large liquid eyes, they pleaded with every fiber of their being and were impossible to resist, even though feeding them the biscuits was rather like posting letters, so rapidly were they downed. After observing this handout for some time, Shmetty [an orphaned infant elephant] decided she should have one as well. It was hilarious to watch, as she clearly had absolutely no idea what to do with a biscuit, waving it around in her trunk, popping it in and out of her mouth and her ear and finally sucking it up in her trunk until it got blown out in an elephant sneeze, making us all jump.

Could you divulge your biscuit recipe?

Teatime during our Tsavo years was indeed a special ritual. The biscuit recipe is that of my grandmother:

Sheldrick’s Tea Biscuits

½ lb sugar

½ lb margarine or butter

1 lb. flour

1 dessert spoon baking powder

pinch of salt

2 eggs

Cream together sugar and butter, add the eggs, work in the flour, baking powder and salt to a rolling consistency. Roll the dough out. Add either nuts, raisins etc., if wanted, and cut into shapes. Bake in a moderate oven until lightly brown.

Taking Action

Your book details numerous waves of elephant poaching in Tsavo over its history. Again, the Tsavo area faces unprecedented levels of poaching. What needs to be done to reduce poaching? What can the average person do to help?

The poaching in Tsavo today is probably worse than it has ever been. To control it requires a two-pronged approach: radical penalties at this end for poaching perpetrators (perhaps even the death sentence as elephant populations run out); and the international community to shame the consumer countries into curbing their appetite for ivory, plus a very strong effort to rein in the international syndicates of smugglers, who also deal in drugs, etc.

Everyone can do something by raising awareness of the poaching crisis, and by raising funds to help those who are able to make even a small difference at the field level to protect and preserve the elephants. Otherwise, elephants could be extinct in the wild within the next 15 years.